[column size=three_quarter position=middle ]

A normal school day in February 1977…

[dropcap size=small]F[/dropcap]eb. 17, 1977 — It was the day of the big game. Two county rivals facing off on the hardwood that night. Tensions were high.

Red, white and blue clad students filed into the gym for a pep rally. Junior William Anthony Shealy entered through the gym doors, crammed with students in the tiny space. A small scuffle ensued, but it was quickly resolved — that is, until the end of the pep rally.

Once the pep rally had ended, the fight began again. And then it got worse.

Ten students, both White and African-American, began brawling in the hallways. Soon it grew to as many as 60. In the fray, one student pulled out a knife and stabbed Shealy twice as Shealy attempted to break up the disturbance.

The school was plunged into confusion.

State highway patrolmen and local prison guards were dispatched to the school to stop the fighting and set up a roadblock in front of the school. Teachers fled to their classrooms and locked the doors. School officials worked to evacuate the school, afraid of further tension.

Black students began boarding buses at 11 a.m. Three students were taken to the hospital for treatment.

The next day, normally noisy halls were quiet. Students who daily filled the hallways remained at home, fearing for their safety. There were no lessons on history, math, science or literature. There was no county basketball match-up. There was only silence.

West may have come a long way since that morning in February almost 40 years ago, but some would argue that racism still exists in area schools.

And racial incidents are not just a thing of the past. At nearby Brevard High School in November, a story of the race-related bullying of a Black student led to three men being charged with ethnic intimidation and concerns raised by parents at Transylvania Schools Board of Education meetings.

The situation at Brevard allegedly started out as an argument over a student’s girlfriend and escalated to the three men driving to the Black student’s house and yelling racial threats. Police reported that the three men were wearing ski masks and carrying knives, a rope and a stick.

The FBI and the local chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People are now investigating the incident and determining whether the three men should be charged with racial intimidation, North Carolina’s designation for a hate crime.

The recent incident at Brevard raises questions. Could it happen in the Henderson County Public Schools? Is the occasionally uttered racist rhetoric evidence of a systemic problem or simply isolated incidents of bigotry?

Differing views on diversity and discrimination

[dropcap size=small]“I[/dropcap] would probably say every minority student at West has (experienced racism),” senior Tyreke Dunbar, an African-American student, said. “Earlier in high school, I encountered more racism than I do now. Freshman year there were a lot of seniors and juniors who thought they were hot stuff and (said some racist things).”

Listen to Tyreke Dunbar’s full interview here:

[soundcloud url=”https://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/259479295″ params=”auto_play=false&hide_related=false&show_comments=true&show_user=true&show_reposts=false&visual=true” width=”100%” height=”450″ iframe=”true” /]

Students and administrators disagree over whether an incident similar to the one at Brevard could happen at West. Dunbar said he believes it is possible.

“I could guarantee that it’s possible to happen here,” Dunbar said. “Tensions can rise pretty fast in a situation, and there are enough white people here and enough black people here for something like that to happen.”

“I would probably say every minority student at West has (experienced racism),” -Senior Tyreke Dunbar

Principal Shannon Auten said she believes it is unlikely an incident like the one at Brevard could happen.

“I feel like this is a welcoming community. I’m so proud of West Henderson. We embrace the diversity we have,” Auten said. “Obviously, we’d never want something like that happening at West Henderson. I just want all of our students and teachers to be nice.”

Senior Caitlin Fuentes, who has a Hispanic parent, believes racism may not be readily apparent inside the hallways of the school, but off-campus it is more prevalent.

“Oh, racism definitely goes on here,” Fuentes said. “Perhaps it’s more outside of school, not in the school — not in the hallways but like on the buses.”

Listen to Caitlin Fuentes’s full interview here:

[soundcloud url=”https://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/259479035″ params=”auto_play=false&hide_related=false&show_comments=true&show_user=true&show_reposts=false&visual=true” width=”100%” height=”450″ iframe=”true” /]

Senior Jade Dunbar, an African-American student, said she believes students and teachers at West are friendly overall and that any racism is minimal.

“I can’t say that I have (encountered any racism),” Jade Dunbar said. “There might have been instances where I thought it might have existed, but I was never certain.”

Listen to Jade Dunbar’s full interview here:

[soundcloud url=”https://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/259479064″ params=”auto_play=false&hide_related=false&show_comments=true&show_user=true&show_reposts=false&visual=true” width=”100%” height=”450″ iframe=”true” /]

Perplexing numbers

[dropcap size=small]I[/dropcap]f racism exists locally, then one would expect there would be data to support that assertion. One metric that could show possible teacher discrimination is the number of short-term suspensions categorized by race.

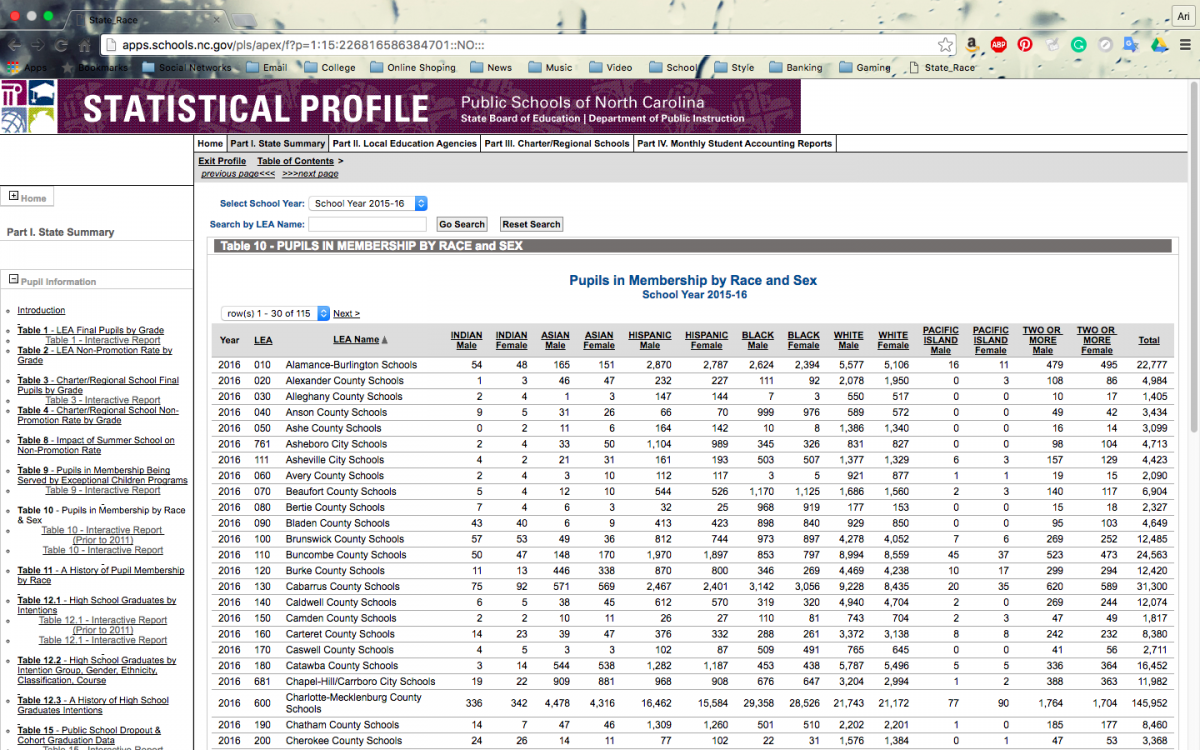

According to a report from the Joint Legislative Oversight Committee of the North Carolina General Assembly, in Henderson County there were 885 total suspensions for the 2014-2015 school year. Of those, 116 involved African-American students or about 13.1 percent of all suspensions for that school year. According to the N.C. Department of Public Instruction, African-American students made up about 3.7 percent of the population of students in Henderson County that year.

Advanced Placement Statistics teacher Tyler Honeycutt said the difference between the number of suspensions and the population could be statistically significant if the data on suspensions and demographics are accurate and from the same time period, but Honeycutt believes it is impossible to tell which school or schools the effect is coming from.

“It is impossible to tell which HCPS school the discrepancy is coming from without further breaking the data down from school-to-school, which the (Joint Legislative Oversight Committee) report unfortunately doesn’t do for us,” Honeycutt said. “Another item that would be good to know is what the offenses that received suspensions were and whether those suspensions were doled out with fairness among racial groups. Again, unfortunately, the data do not indicate whether the punishments were the same for offense types among racial categories. This occurs mainly because students who were sent to the office, but who did not get suspension punishment (ISS, OSS, etc) are left out of the data. This gives us very little by which we can compare practices of disciplinary procedures for different racial groups. To me, that would be the true marker of whether discriminatory practices were in place. I think the questions posed here really illuminate the need for better data-gathering practices regarding school disciplinary procedures in general.”

The discrepancy also occurs with other minority populations. For multi-racial students there were 69 suspensions for the 2014-2015 school year or roughly 7.8 percent of all suspensions for that year despite multi-racial students making up 3.6 percent of the total population. Multi racial students face some of the same pressures minority students do. Fuentes said being bi-racial puts her into an awkward position that has sometimes led to her feeling discriminated against.

“I was put into ESL in elementary school, which is funny because I speak English perfectly. It’s my first language. I don’t really speak any Spanish at all,” Fuentes said. “They saw my skin color and said, ‘Oh you should be in ESL.’ It made my mom really mad. I was kind of too young to understand, but now when I look back I’m like, ‘Really, guys, just talk to me, and you can see I speak English just fine.”

“They saw my skin color and said, ‘Oh, you should be in ESL.’” – Senior Caitlin Fuentes

Henderson County is not alone in facing these racially disproportionate suspensions. A 2014 study by the University of Pennsylvania graduate school of education found that disproportionate punishment was systemic throughout the southern United States. In North Carolina alone, the study found that “65,897 Black students were suspended from North Carolina K-12 public schools in a single academic year. Blacks were 26% of students in school districts across the state, but comprised 51% of suspensions and 38% of expulsions.”

The study also linked these types of punishments to the “school-to-prison pipeline,” a term used to describe the increasing patterns of contact students have with the juvenile and adult criminal justice systems as a result of the practices implemented by educational institutions. In its conclusion, the report laid out possible ways to diagnose the problem of disproportionate punishment.

“In most teacher education and administrator preparation programs, too little emphasis is placed on racial disproportionality in discipline and ways educators help sustain the school-to-prison pipeline.” The report’s conclusions states, “More time and attention must be placed on educating aspiring teachers and school leaders about implicit bias and other racist forces that annually reproduce horrifying statistics such as those presented in this report.”

Auten said any perception of discrimination is unintentional.

“I think in Henderson County Public Schools and at West our goal is to treat each student and each disciplinary situation in a fair and consistent manner,” she said. “Every situation is different. If we are making this a place where we embrace everyone for their differences, we also have to be fair and consistent with our discipline.”

Another important metric to consider is the diversity of the school’s student body. According to Startclass, a service that ranks high schools and colleges based on academic performance, in the 2013-2014 school year, 87.1 percent of West students were white with the next largest group being Hispanics at 6.9 percent of the population.

There was a difference between the graduation rates of white and minority students for that year, according to Startclass. The Caucasian graduation rate at West that year was 95 percent while the Hispanic and multi-racial graduation rate was 80 percent — three percent less than the state average. However, there was not a significant discrepancy in math and language arts standardized test scores for that year.

A Southern school in a diverse world

[dropcap size=small]D[/dropcap]espite the numbers, Auten has faith that West is a diverse place for students to come to school.

“Diversity to me is based on culture and ability, gender, race, ethnicity, identity and expression, political affiliation, religion, sexuality, sexual identity and all sorts of different things. I feel like West is a diverse place,” Auten said. “What I’m really proud of is the way our students really embrace and accept each other. I feel like this is a welcoming community. I’m so proud of West Henderson.”

Jade Dunbar said she would like to have attended a more diverse school, but she believes West is becoming more diverse.

“I feel like it would be better if it became more diverse, but we are becoming more diverse as the years go on,” she said. “We’ve come pretty far since my freshman year. Now that we’ve had all these new African-American students, new Asian students and new Hispanic students, it’s made everything a bit more equal.”

“Diversity to me is based on culture and ability, gender, race, ethnicity, identity and expression, political affiliation, religion, sexuality, sexual identity and all sorts of different things. I feel like West is a diverse place. What I’m really proud of is the way our students really embrace and accept each other. I feel like this is a welcoming community. I’m so proud of West Henderson.” -Principal Shannon Auten

Tyreke Dunbar would have liked attending a more diverse school, but he also feels it isn’t an issue. “I think it would be a lot cooler for just about every aspect of our school if there were more of a diversity around it,” Dunbar said. “It’s not too bad, though.”

But both Jade and Tyreke Dunbar agree racism is still a problem in American society. “It’s pretty ignorant to ignore the fact that there is racism around black people,” Tyreke Dunbar said. “People still try to act like it’s not a big deal. It still is. It’s just not in the same way that it used to be.”

By Ari Sen

Correction: The Wingspan Staff previously misidentified Mr. Shealy as African-American. We regret the error.

[/column]