Sophomore Michaela Bradley sat down in her ninth grade health class last spring on the morning her teacher would begin the sex education lessons. She expected to be uncomfortable like she had felt in her health classes at Rugby Middle School.

She was pleasantly surprised when the atmosphere in her high school health class proved to be different from what she had anticipated.

Her teacher was more open about the topics being discussed, and the students more accepting of opinions and questions.

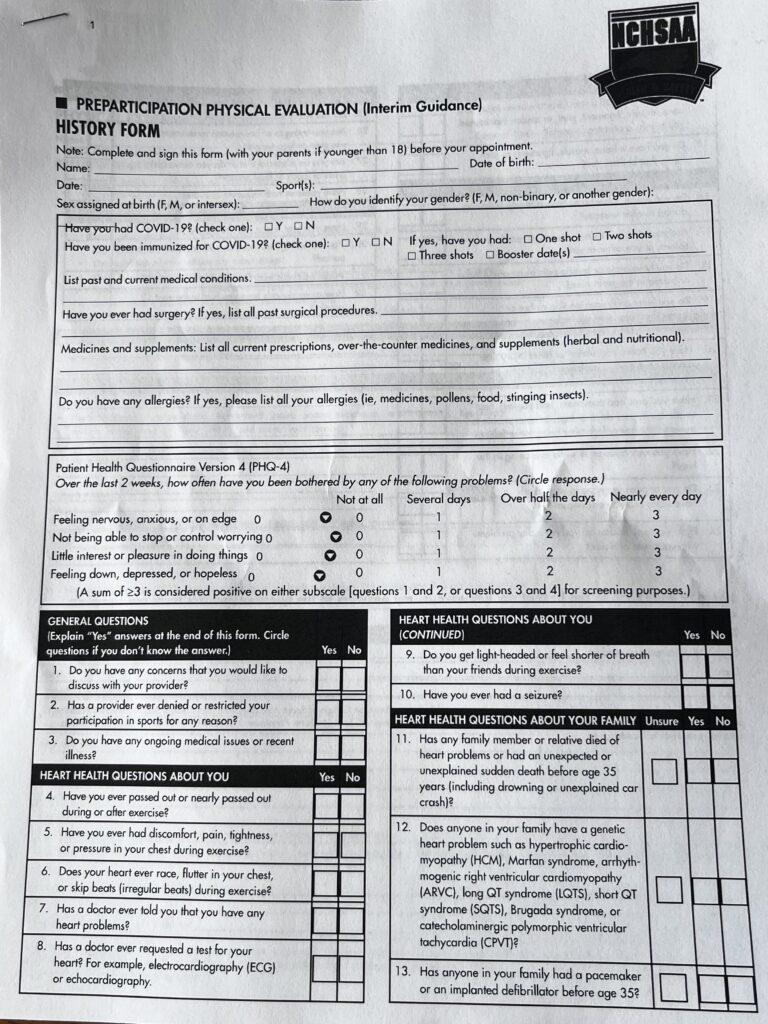

North Carolina General Statute 115C-81 states that “reproductive health and safety education must provide factually accurate biological or pathological information that is related to the human reproductive system. Materials used must be age appropriate, objective and based upon scientific research that is peer reviewed and accepted by professional and credentialed experts in the field of sexual health education.”

The state’s sex education curriculum taught in ninth grade health classes shifted from a comprehensive program to an abstinence only curriculum in the late 1990s. Currently, an abstinence-based curriculum also includes the effectiveness of contraceptives, and all scenarios are presented in the context of marriage.

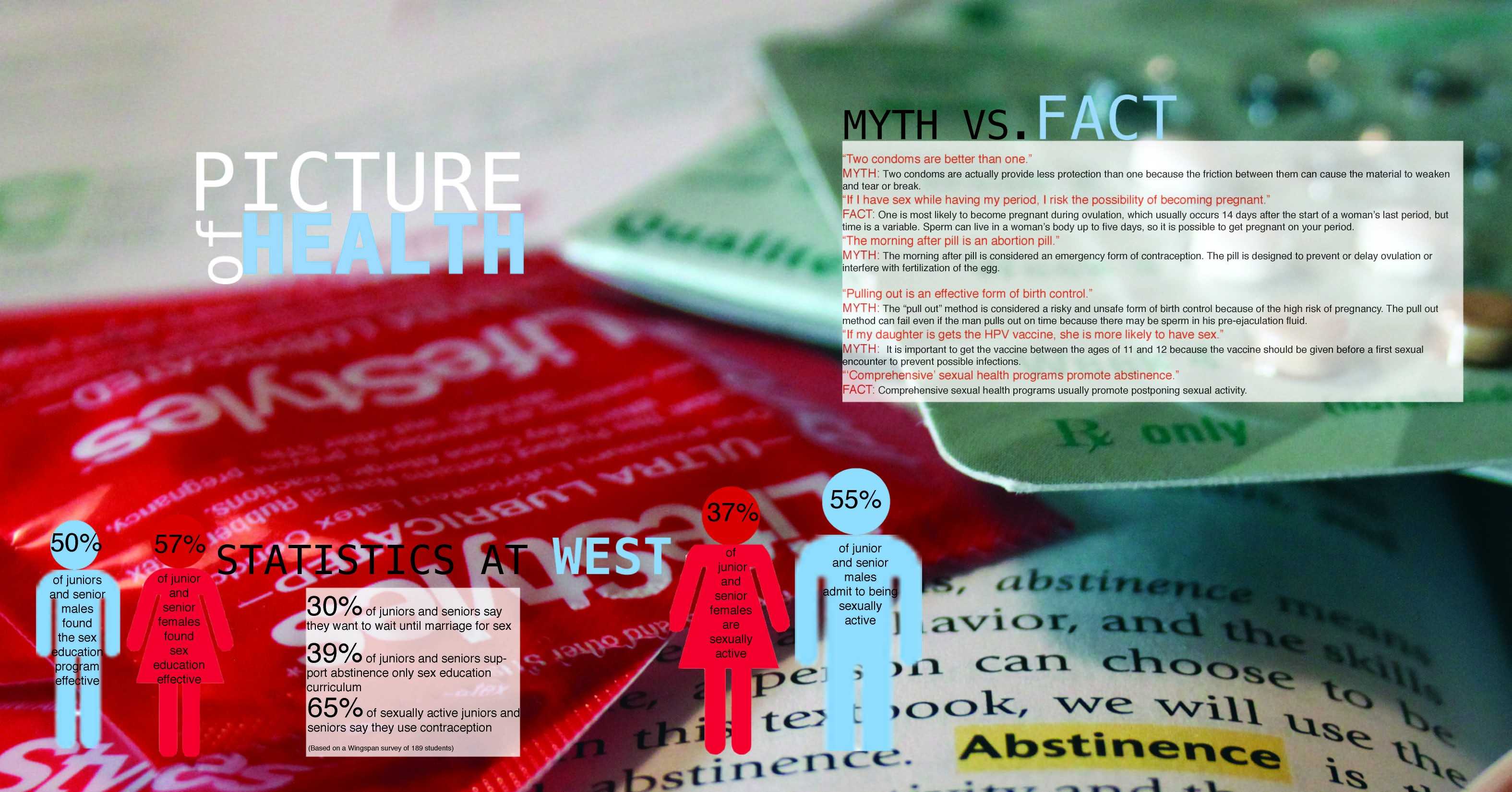

While Bradley and her peers have found the high school class to be more open than their middle school sex education classes, only 46 percent of the students at West indicated the curriculum was helpful and effective on a Wingspan survey of 189 students.

“We do anatomy, male and female. I think that’s important because of what they do not know about their own bodies. It’s quite interesting to see what they don’t know,” health teacher Allyson Warren said. “We go over contraceptives and about how effective they are, and we discuss sexually transmitted disease (STDs). At this point I feel that it’s pretty accurate, and it’s pretty well based. I think everyone leaves my class a little more aware.”

According to Bradley, teachers at West know how to address the topics in an informative and comfortable manner.

“I still get nervous about the class because it is a subject that is normally not approached in the way that sex ed approaches it,” Bradley said. “I feel like once you’re in high school, you’re more mature and able to handle it.”

According to Bradley, even the more comprehensive curriculum may not present essential information to teenagers. Bradley said students today are facing topics not covered in the textbooks.

“I feel like the books that they use are outdated and they need more recent books,” Bradley said. “Some of the issues aren’t as true for our generation.”

According to former Planned Parenthood sex educator Sally Phillips, the seventh and eight grade curriculum she taught for 30 years was an abstinence-based program similar to the one taught in North Carolina today. Although the curriculum is more comprehensive than previous abstinence-only curriculum, Phillips said she would support changes.

“I would make it more realistic. We had a lot of barriers put upon us. We were not allowed to talk about all of the options available to somebody when they’re experiencing an unplanned pregnancy,” Phillips said. “We were required to stay away from controversial topics like homosexuality or abortion.”

Warren said she believes teenagers often feel invincible when it comes to sexual behavior, illegal drugs and dangerous driving.

“Students take from it (the sex ed lessons) that ‘I may or may not be doing this, but now I realize that this can really happen to me.’ I think we are all guilty of that (thinking we are invincible) even as adults,” Warren said. “It’s really prevalent with kids who think, ‘I can text and drive, I can have multiple sexual partners and not have an STD, I can have sex with my boyfriend however many times and not get pregnant.’”

According to the Centers for Disease Control, 46.8 percent of high school students have had sexual intercourse by the time they graduate.

According to Bradley, the current sex education curriculum does not go into depth in the subjects that are taught, and this can be a bad thing for students who do not have parents to talk to them about it at home.

“I feel like there are more things that they could have taught us about, but in general I feel like that they give us a good enough base to do our own research on top of it,” Bradley said.

Health teacher Cathy Corliss agrees that teachers face limits in what they are allowed to discuss.

“I preferred the older, more comprehensive curriculum, but I think we’re better off now than we were a few years ago,” Corliss said. “For a while we used a book called TeenAid, which was an abstinence-only curriculum. It was a hard book to read and difficult to instruct out of. We just didn’t like it very much.”

Corliss said that teaching students about anatomy is vital to their understanding of sexual health. She believes that what they teach is effective, although it can get discouraging.

“It hurts when you see students that were in your class become pregnant,” Corliss said. “But I think that sharing the experiences of students and how it can change your life is thought provoking.”

According to Corliss, contraceptives are an important component of sex education. “I tell kids about contraceptives, and if you get married and you don’t want to have kids right away, then you have to have knowledge of those things,” Corliss said. “It’s important to know those things are out there, and we have to teach it in the context of marriage. I feel we’re leaving the group of students out that are sexually active.”

By Olivia Slagle and Emily Treadway